Socio-economic factors in the endurance of Ayrshire’s male-dominated bonnetmaking industry into Scotland’s Industrial Age: A comparison of the Dundee and Stewarton guild experiences

Michael Harrigan

Dissertation submitted as part requirement for the MLitt in Scottish History by Distance Learning at University of Dundee.

27 February 2024

Please note that this study is ©Michael W. Harrigan. If referenced as a resource for academic purposes, the following citation should be used:

Harrigan, Michael W., ‘Socio-economic factors in the endurance of Ayrshire’s male-dominated bonnetmaking industry into Scotland’s Industrial Age: A comparison of the Dundee and Stewarton guild experiences’ (Unpublished MLitt dissertation, University of Dundee, 2024); https://www.thismanknits.com/early-male-hand-knitters-scotland/

Declaration

I, Michael Harrigan, declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. Unless otherwise stated, all references cited have been consulted by me and the study of which this dissertation is a record, has also been carried out by me. This dissertation has not been previously accepted for a higher degree.

27 February 2024

Abstract

This study examines the male-dominated hand-knitting industry in Scotland from the earliest bonnetmaker guild formation in the late fifteenth century through the introduction of machine knitting in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Specifically, a comparison is made between the bonnetmaking guilds of the burgh of Dundee and the small Ayrshire town of Stewarton in respect of their management of members, products and markets. The two guilds were chosen as subjects for this research as they were the only incorporations in Scotland that exclusively produced headwear.

The flat, oversized blue bonnet so popular with the Scottish working man, which was their original product was likely copied from similar headwear worn by French clerics who travelled between the European continent and Dundee. The bonnetmakers of Dundee relied excessively on the domestic market for their income, and when that market declined, so did their fortunes. The Stewarton craftsmen, on the other hand responded to the market decline with the introduction of a new product – the nightcap – to address changing consumer preferences and later were able to capture the lucrative market in military headgear, showing additional ability to adapt. Their success continued with the export of their popular products to new markets in North America during the latter years of the eighteenth century. Bonnetmaking by hand came to an end in the second half of the nineteenth century, when knitting by machine took precedence.

Available documents from the period – including guild and court records and wills and testaments, for example – were consulted in considering the reasons for the downturn in bonnetmaking in Dundee in the mid-eighteenth century and the upsurge of production in Stewarton. Weaknesses in the Dundee organisation and a lack of entrepreneurial spirit – in failing to consider new products and markets – are compared to the better-organised guild in Stewarton and its successes in introducing products to meet changing demand and seeking additional domestic and international markets.

Acknowledgements

I would especially like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Graeme Morton PhD, Professor of Modern History and Director of the Centre for Scottish Culture at the University of Dundee for his enthusiastic support of this endeavour and for his insight, guidance and many helpful recommendations that have helped me improve this final project.

Seventeenth century court minutes and wills and testaments written in Scottish Secretary Hand presented a host of challenges for me. Whenever a problem arose, Jenny Blain PhD, Dundee, writer and independent researcher, genealogist and poet, and acting chair of the Tay Valley Family History Society council very generously made her expertise available. For that I am most grateful.

From the early days in identifying a topic for my research, Carol Christiansen PhD, Curator and Community Museums Officer at Shetland Museum and Archives in Lerwick provided encouragement to me in pursuing the work of the bonnetmakers – the first male knitters in Scotland. I am most appreciative of her guidance on getting started and her support along the way.

To the many archivists, librarians and volunteers at historical societies, who have cheerfully responded to my many emails and questions along the way – a special thank you.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Acknowledgements

List of Tables

List of Figures

Introduction and an Overview of Bonnetmaking in Scotland

Chapter 1:

Bonnetmaking in Dundee and its Decline in the Eighteenth Century

Chapter 2:

Stewarton Bonnetmaking and the Role of the Local Bonnet Court in the Trade’s Success through the Eighteenth Century

Chapter 3: Product and Market Diversification and the Endurance

of Stewarton’s Bonnetmaking into Scotland’s Industrial Age

Conclusion

Bibliography

List of Tables

Table 1: Dundee bonnetmakers: frequently occurring surnames

Table 2: Stewarton bonnetmakers: frequently occurring surnames

List of Figures

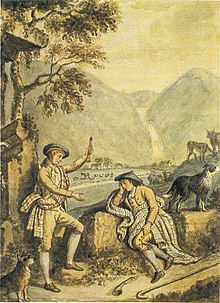

Figure 1: The Craigy Bield, by David Allan. Two Lowland shepherds of the 18th century, wearing variations on the blue bonnet. Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Figure 2: Bonnet re-creation by author. Photographs ©Michael Harrigan

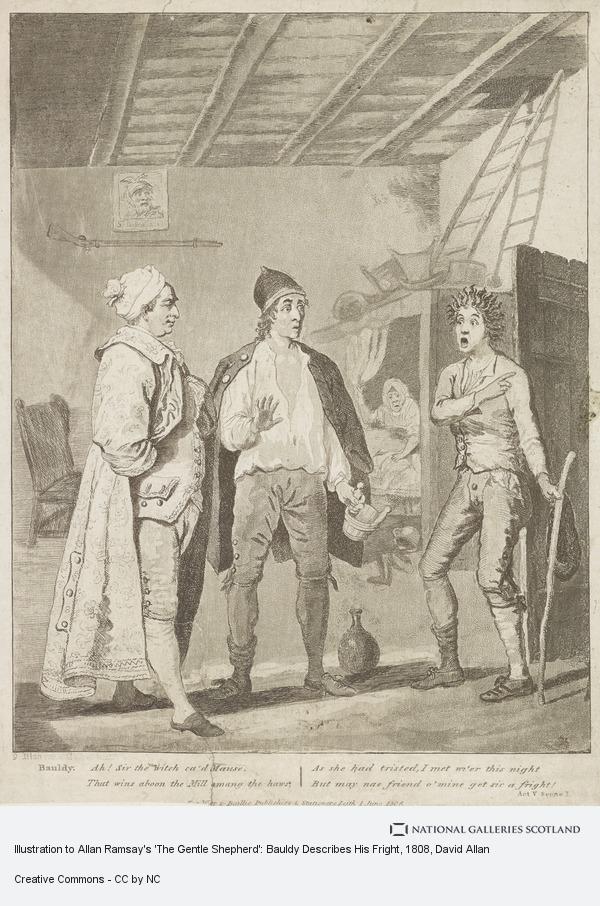

Figure 3: David Allan’s Illustration to Allan Ramsay’s ‘The Gentle Shepherd’: Bauldy Describes His Fright. Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Figure 4: Soldiers from a Highland regiment c. 1744. Artist unknown, public domain

Figure 5: Glengarry, Regimental Museum of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, Stirling Castle. Acc. No.0007a Date c.1854

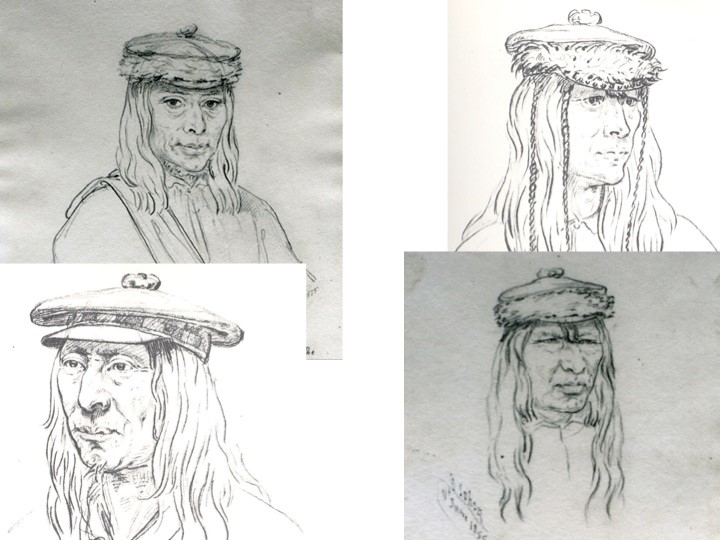

Figure 6: Four sketches of Native men by Gustav Sohon in the 1850s – all variations of Scots bonnets, some with fur bands added: https://frenchinwisconsin.couleetech.com/2013/12/10/scots-bonnets-in-canada-and-the-west/

Introduction and an Overview of Bonnetmaking in Scotland

It is not known why or how men came to knit the large flat bonnets that would become the iconic headwear of Scotland’s labouring classes but it is known that the men organised themselves into professional craft associations as early as the late fifteenth century and were able to provide for themselves and their families from the production of hand-knitted items. Long before knitting was practiced as a domestic pastime by women in Scotland, the bonnetmakers of Dundee were the first to incorporate as a guild to protect their craft. It was considerably later that the bonnetmakers of Stewarton, who developed new products, distribution networks and overseas markets formed their organisation, which would endure while bonnetmaking in other parts of Scotland died away.

Guilds, specialising in the production of hand knit clothing had been formed in Europe as early as the fourteenth century.[1] By the early sixteenth century, hand knitters in France were producing woollen caps and stockings.[2] There were significant differences, however in the requirements established by guilds in central Europe compared with those of Scotland: whereas knitters in Europe were required to produce elaborate knitted carpets as the final step in achieving master craftsman status, Scotland’s bonnetmaking guilds had a more narrow focus, requiring perfecting the knitting of a bonnet to specifications.[3]

The bonnet became popular among working-class men in both the Lowlands and the Highlands, as it provided protection for the head and face in Scotland’s inclement weather.[4] According to T.C. Smout, in its day the bonnet was so ubiquitous that it was ‘…even more a mark of Scottish identity than the plaid…’[5] Its prevalence was written about by Robert Ashley Cooper, in his dissertation on the Hummel bonnet; and by Stana Nenadic, writing about clothing in the long eighteenth century.[6] [7] The bonnet’s popularity lasted well into the eighteenth century.

By the mid-1700s bonnetmaking in Dundee was in serious decline while the craft was on the rise in Stewarton. To contextualise this change this dissertation will address the likely origin of the bonnet, how it was made, the beginnings of the craft and its incorporation in Dundee and the transition of the locus of production and development to Stewarton in the latter half of the eighteenth century. Specifically, three questions arise –

- To what extent did internal guild factors contribute to the decline of Dundee bonnetmaking by the mid eighteenth century?

- How did the Baron Court of Corsehill factor in Stewarton’s bonnetmaking success through the eighteenth century?

- In what ways was the Stewarton bonnetmakers’ diversification of products and markets responsible for its survival into the Industrial Age?

The Scots bonnet likely had its origins in continental Europe and made its way to Scotland as early as the fifteenth century – at a time when the flat bonnet was the style worn by men throughout the French countryside.[8] French clerics, who travelled back and forth between the continent and Dundee, wore a flat black cap similar to the type that would eventually be fashioned into the blue bonnet – the headgear of the labouring classes of Scots men from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries.

Figure 1: The Craigy Bield, by David Allan. Two Lowland shepherds of the 18th century, wearing variations on the blue bonnet. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Beginning in the early 1980s Helen Bennett wrote extensively on the subject of early hand knitting in Scotland and bonnetmaking in particular.[9] A decade later, Enid Gauldie captured the Dundee bonnetmaker experience. In The Bonnets of Bonnie Dundee, she opines that the bonnet’s origin was likely in the flat black caps worn by priests in France –

Wishart and Knox and their predecessors travelled between Europe and Scotland bringing back the latest introductions to the world of ideas. It seems quite likely that these well-travelled priests brought back fashions in dress as well.[10]

She adds that the important trading centre of Dundee was first to adopt the style and in so doing saw the birth of an industry: ‘Dundee had found a new product…It had everything. It was sensible, practical, smart, easy and cheap to produce.’[11]

Bonnets were made from the skin wool of slaughtered sheep, meaning that the craft did not compete with domestic requirements for raw wool from the shearing of live animals. The wool was dyed blue using plant leaves – and later with indigo from India when that became available. It was spun and then the bonnet was knit by hand in a circular manner starting with a narrow headband and finished with a flat crown: it was knitted considerably larger than the intended finished size and then felted so the bonnet would repel water and shrink in size. The desired shape and final size were achieved by stretching the bonnet over a circular form: when dry a steel brush was used to raise the pile and the bonnet was shaved for smoothness. The finished bonnet was approximately twelve inches in diameter, with the flat top or crown typically broad enough to provide the wearer some protection against the rain.[12]

Figure 2: Bonnet re-creation by author. Photographs ©Michael Harrigan.

Although there were a number of processes to be mastered in the production of the bonnet, the bonnetmakers were not considered to be among the most skilled of craftsmen. At least in the earlier days they produced lower quality knitted items that were aimed at the domestic market.

Dundee men and their families produced bonnets in their homes. Gauldie describes the domestic scene: within a bonnetmaker’s humble cottage were ‘the boiling vats, the barrels of urine, the skeins of wet wool hanging up to dry’.[13] When dry the wool yarn was knitted into bonnets, which were sent to a waulking mill to be shrunk and felted and returned to the cottage for finishing. It was in this manner that the burgh’s men were supplied with bonnets and through the local market to those living beyond the burgh in ‘the hills and glens of the wide Angus hinterland and probably farther afield’.[14]

Annette Smith authored The Nine Trades of Dundee in the mid-1990s and provides additional detail about the guild experience.[15] By the end of the fifteenth century the bonnetmakers of Dundee had formed the first guild of its kind in Scotland – to ensure that outsiders would not be able to encroach on their territory and disrupt their source of income.[16] The guild was granted a Seal of Cause, creating a monopoly on practising its craft within the burgh, and owned a Lockit (Locked) Book containing its trade secrets and the names of its masters.[17] A trade secret, which the bonnetmakers’ book did not contain was the method by which bonnets were made: a description of required weights and sizes for finished bonnets appears in journeymen’s agreements, but seemingly nothing more.[18] In the sixteenth century guilds were established in Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Perth, Stirling and Glasgow – and somewhat later in Kilmarnock and Stewarton. Only the Dundee guild in the east and Stewarton in the west, however produced headwear exclusively, and for this reason are the subject of the comparison undertaken in this dissertation.

Chapter 1 considers the reasons for the decline in Dundee’s importance in bonnetmaking – internal and external to the guild structure. Bennett and Gauldie both note that bonnetmaking in Dundee had reached a state of insignificance by the mid-eighteenth century.[19] Alex. Warden, in The Burgh Laws of Dundee writes that the number of bonnetmakers had dwindled to four by 1783.[20] T.R.S. Campbell in A Short History of the Bonnetmaker Craft of Dundee, refers to the reduced use of the Balmossie waulking mill as an indicator of the waning of the craft: ‘the mill was abandoned in 1784’.[21]

A change in consumer preference has been cited as a reason for the decline: men had abandoned the bonnets for hats.[22] Nenadic writes that this change in fashion came with new prosperity – that by the end of the eighteenth century even male servants in the countryside had foregone the flat bonnet for a tall hat.[23] The reasons were wide-ranging, however: difficulties in managing external competition, failing to seek new markets and an inability to adapt to changing market requirements seem attributable to internal guild factors.

Gauldie suggests that the decline began in the mid-seventeenth century with the siege of the city by General George Monck –

…which left buildings and harbour wrecked, the population decimated…records, tools, materials, burned or pillaged. It was nearly ten years before the bonnetmakers gathered their strength to reconstruct their craft incorporation, to buy a new Lockit Book in place of the one that had been destroyed, to begin again the encouragement and regulation of their trade.[24]

She posits that as a result the bonnetmakers were not prepared to take advantage of new opportunities, having ‘neither the capital, the resources nor the spirit of entrepreneurship’ necessary, adding that ‘…the second half of the seventeenth century was a time of depressed trade and little hope’.[25] Government grants, which were made available following the Union of 1707 saw a change in fibre focus – linen rather than wool – underpinning a new industrial base for Dundee.

In Chapter 2 the upsurge in Stewarton’s bonnetmaking and the role of the local bonnet court in the craft’s success is addressed. Additionally, the functioning of the local guild structure is compared to that in Dundee. As the eighteenth century progressed membership in Stewarton’s guild continued to grow and the bonnetmakers were producing beyond local requirements. The Baron Court of Corsehill – the bonnet court – has been credited with providing the structure and support that contributed to Stewarton’s success, from the early seventeenth century through the late eighteenth. The court’s oversight was essential to the orderly conduct of trade: it appointed inspectors to ensure the overall quality of products. Helen Bennett and Miriam Lamont both write of this noting that the quality of the wool, the dyeing of it, the weight of the bonnet and the standard of finishing were closely monitored.[26] When demand for bonnets was poor, ‘idlesetts’ or pauses in production were enacted by the court. The deacon of the court, through his bailie, handed out punishment for breaches of the regulations and unlawful acts:

A particularly severe punishment – a fine of £50 Scots and permanent expulsion from the Incorporation – was reserved for those who bought bonnets in Kilmarnock and sold them in Glasgow.[27]

The court settled local disputes and was involved in social issues, such as providing assistance to the poor of the craft as well.

The relationship of the Stewarton bonnetmakers with the Glasgow guild is explored in Chapter 3, in respect of the development of domestic and international markets for Stewarton’s headwear. In 1650 the court negotiated a licence for the Stewarton guild to sell their bonnets in Glasgow markets, bypassing restrictions against outsiders selling goods within the burgh, and for exporting their goods through Glasgow, establishing trade with the Americas.[28] Bennett, in writing about the Glasgow guild, notes there were indications ‘that the Craft there was never very strong’.[29] That Stewarton’s output exceeded local requirements was undoubtedly a stimulus toward seeking such an arrangement.[30] By the middle years of the eighteenth century trade with northern Europe was stagnant: Stewarton’s bonnetmakers again capitalised on the relationship with Glasgow. Glasgow’s westward shipping trade had become predominant, opening early overseas markets for Stewarton’s bonnets – including the Scots in Ulster and later settlements in Atlantic Canada, most notably Nova Scotia.

At the same time, consumer requirements were changing and the longevity of Stewarton’s production lay in its recognition of the need to develop new products. As Gauldie notes: they were able to ‘make trade where none had existed’.[31] During the 1720s Ayrshire bonnetmakers experienced a downturn in demand for bonnets and created a new product – a nightcap – a bell-shaped cap that became part of the ‘everyday dress of working men and sailors and an important component of their trade’.[32] Their early successes and support of the bonnet court prepared them to capitalise on changes in fashion preferences and emerging markets – including further expansion into producing military headgear. Cooper notes that the blue bonnet had become associated with the Highlanders and after the 1745 uprising became part of the military uniform of ‘highland companies in the service of the crown’.[33] According to Lamont ‘Stewarton was most famous for its regimental beret-style hats, including the Glengarry, the Balmoral and the Tam o’Shanter, which all met the rigorous Ministry of Defence requirements.’[34]

Bennett writes that by the 1790s Stewarton had developed a significant export trade with North America, and that although demand was anything but consistent, at times ‘orders were substantial, and usually required in a hurry’.[35] Demand for the new products led to an increase in membership in the Stewarton guild, which still maintained direct control over production.

By the beginning of the second half of the nineteenth century, the introduction of knitting machines made it possible to supply the increasing requirements of the military for headgear – but is was also the death knell for bonnet knitting by hand. Bennett notes that by this time bonnetmakers were beginning to work in factories, but it wasn’t until the 1870s that the actual knitting was being done by machine.[36] As Gauldie writes – ‘Bonnet making by hand did not survive the industrial revolution’.[37] But it did survive well into the period of Scottish industrialisation.

The writing of Bennett on bonnetmaking across Scotland, the work of Gauldie on Dundee bonnetmaking, Smith’s writing on the trade guilds of Dundee and Cooper’s work on the bonnet as military headgear led to an examination of primary sources from the period. In addition, the iconic bonnet will be viewed in the context of challenges to the guild system and the introduction of new technologies and the development of consumerism – particularly through the writing of Jan de Vries, Stana Nenadic and Irena Turnau.[38]

Chapter 1:

Bonnetmaking in Dundee and its Decline in the Eighteenth Century

Although the bonnetmakers of Dundee incorporated their craft in 1496 it has been suggested that they were knitting bonnets as early as the twelfth century.[39] Whether that early a date is accurate or not it is reasonable to assume that they were engaged in bonnetmaking from at least the mid-fifteenth century and felt a need to organise to protect their craft a few decades later. From early on the bonnetmakers’ practical product was popular with working-class men: the felted fabric of the bonnet meant that it was virtually waterproof and the large circumference of its crown helped keep the wearer’s face relatively dry in rainy weather. Bonnets were sold in Dundee’s burgh market, where there was a steady stream of customers including

…those who already came into Dundee markets to sell goods or raw materials from the countryside. The suppliers of wool, barley, meat, whisky, fish and pottery and salt probably account for the reported widespread distribution of Dundee bonnets…[40]

Enid Gauldie notes that although the number of bonnetmakers in Dundee was never large, they were able to supply a significant part of the country with headgear for nearly three centuries.[41]

When the main consumer of their product began to follow a change in headwear fashion, Dundee’s bonnetmakers were not prepared to adapt to this new requirement. Men had abandoned bonnets for hats: by the latter part of the eighteenth century even the working man in the countryside was wearing a tall hat.[42] Nor were they prepared to take advantage of alternative markets at home or abroad: in the mid-eighteenth century the military headgear market became more demanding, particularly in requirements of variety and quality and it was the bonnetmakers of Stewarton who secured this important business.[43] This chapter attempts to answer the question: To what extent did internal guild factors contribute to the decline in Dundee’s bonnetmaking by the mid-eighteenth century?

Craft guilds across Scotland were granted privileges that were much the same: each was given a monopoly on trading rights, the right to establish a governing body and the right to enter into apprentice or indenture agreements. In fact, as Ebenezer Bain writes, the guild system wielded significant power: ‘…all the journeymen, servants, and apprentices in the town, as well as the members proper, came within the jurisdiction of the deacons and their courts’.[44] One might expect the functioning of one guild of bonnetmakers to be similar to that of any other guild. However, it will be seen in this and the subsequent chapter that the overall management of production, and of relationships – both within and outwith the guild – did in fact differ significantly from one incorporation to another, and this may well help explain continuing success or the lack of it.

From the period beginning with the Dundee craft’s incorporation until the mid-seventeenth century little information on the craft is available owing to the destruction of its records during the Anglo-Scottish War:

The original Seal of Cause and Charter of the Incorporation are lost…The first Locked Book of the Craft, which contained a register of the admission of the masters and apprentices, and the acts and statutes enacted for the guidance and well-being of the body, was destroyed at the storming of the town by Monk on lst September, 1651.[45]

The bonnetmakers’ new Lockit (Locked) Book dates from 1660, and members of the craft at that time entered as much detail as could be remembered about past masters.[46] In addition, an act dating to the late sixteenth century indicates that at least some of the pages of the original book were recovered: ‘It records a decree of the Craft of 28 July 1541 that no apprentice was to be taken on without being entered in the book…’[47] Beginning with the inauguration of the new book names of all new craft masters have been entered.

According to Helen Bennett, there was a reasonably stable number of members entering the guild from 1660 – including 12 in the 1660s and 11 in the 1680s.[48] In all, from 1660-1788 there were 88 admissions: the lowest number (three) occurred in the 1780s and the highest (15) in the 1720s; 65 of these admissions were sons of masters and 10 were sons-in-law.[49] It is notable that in 1783 there were only four bonnetmakers listed – and more than 100 weavers in Dundee by comparison – and ‘…the last actual maker of bonnets to enter signed the Lockit Book in 1790’.[50] By this time the craft, which had long provided a living for bonnetmakers in Dundee was coming to a close – and employment in the weaving industry was on the rise.[51]

As can be inferred from the sons of and sons-in-law numbers, membership was controlled by a small number of families: three family surnames represented half of the membership as can be seen in Table 1 below.[52]

| Bonnetmaker Trade Lockit Book 1660-1788 | ||

| Surname | Number of members named | Percentage of membership |

| Hog(g) | 17 | 20 |

| Langlands | 17 | 20 |

| Gib | 8 | 10 |

Table 1: Dundee bonnetmakers: frequently occurring surnames

Gauldie, in The Bonnets of Bonnie Dundee writes of the frequent occurrence of the Hog surname, including some of the women in the family – who were practitioners of the craft but not allowed to become masters:

The first named deacon of the Bonnetmakers was David Hog. His sons and grandsons succeeded him in the craft all the way from 1529 until the end of the eighteenth century without interruption…His daughters, Elspeth and Margaret were also apprenticed to the trade but although they were allowed to practice the craft their names were not written into the Lockit Book.[53]

Apprenticeships were an important part of the guild system, helping increase production and income for master bonnetmakers. Most trades regulated the number of apprentices that a master could engage at one time – not only to provide adequate supervision and training but also to keep the number of guild masters low – preventing an oversupply of bonnets and ensuring a greater share in overall product sales.[54] The experience of the Glasgow bonnetmakers was similar to that of guilds in other jurisdictions: ‘So particular was the Craft regarding the training of apprentices that for many years no master was allowed to have more than one apprentice at a time’.[55] The trade even forbade the engagement of apprentices for periods when the number of masters was too large.[56] In Dundee, a further restriction was imposed in an attempt to control the number of masters in the craft: an apprentice was required to serve for five years before being considered for master status.[57] Typically masters would enter into agreements with the sons (and at times daughters) of craft brethren, stipulating the terms of the apprenticeship – including the period of time and expectations – and recording the agreements in the trade’s records.[58] An example is dated 21 May 1684, between Robert Philip and John Mill, who agreed that Mill’s son Thomas would enter an apprenticeship with Philip for one year at a fee of £5 – with the expectation of his weekly production being 14 great bonnets, 21 six-pound bonnets and 28 four-pound ones.[59] The number of masters – and apprentices – and the production of bonnets continued to be relatively stable through the mid-eighteenth century.

Although controls were in place to regulate the number of guild masters it is generally acknowledged that the craftsmen earned little more than enough to support their families. Bennett notes in Scottish Knitting that ‘…the craftsmen were humble folk who earned at most a modest living’.[60] An examination of Dundee bonnetmaker wills and testaments provides some insight into their lives – at least at the time of their deaths. Between 1600 and 1800 four testaments are available: three are dated 1621 and one a century later, in 1734.[61] The 1621 testament of Andrew Kinman[62] values his inventory and debts owing to him at £92 6s 8d, including four stones of white wool valued at £40 and 30 blue bonnets at £5. The debts owed by the deceased included three items to the skinner for wool at £36, £16 6s 8d, and 21s, £23 to the dyer for his services, outstanding pay to his servants, unpaid bills for wine, ale, fish, baked goods and oatmeal, and rents on leased land for a total of £133 13s 4d. At his death his moveable assets had a negative value of £41 10s 8d. [63] The testament of William Muddie, also from 1621 contains less detail, although among the moveable assets listed are one stone of fine wool, one stone of coarse wool, and finely made blue bonnets – comprising most of the £20 6s 8d value of the inventory. [64] A legal deed and income on land increased the value of his moveable assets to £88. The testament of John Craig is also dated 1621.[65] His moveable assets included a dozen blue bonnets valued at £10, a total inventory value of £23 6s 8d and a moveable asset total of £5 6s 8d after debt service. The tools of the deceased’s trade were not listed individually in any of these testaments, but it is known that they were simple and of little monetary value.[66]

Just over a century later, the 1734 testament of John Hogg – a prominent surname in Dundee bonnetmaking – revealed a moveable estate valued at £852 4s 10d. There is little information on individual items except for merchant goods valued at £533 15s, household furnishings at £183 and unpaid debts owing to the deceased of £134 8s 10d. With so few such testaments available to review it is difficult to conclude that the value of Hogg’s estate was unusual, but it does seem likely that the values of the Kinman, Muddie and Craig moveable estates were more typical.

As an indication of the fortunes of the Dundee masters by the mid-eighteenth century – by which time there was a noted decline in bonnet production – the records of the local waulking mill provide insight. In the mid-seventeenth century the craftsmen rented the local mill to clean and felt their bonnets more efficiently.[67] In 1706-7 approximately 12,000 bonnets were milled and the next year that number nearly doubled – to just under 23,000 pieces.[68] By 1764 the number had dropped to 7,000.[69] This downturn in production aligns with the serious decline in bonnetmaking by the mid-eighteenth century noted by both Bennett and Gauldie.[70]

One contributor to the industry’s decline was the lack of an export market for bonnets. Isabel Grant writes of the poverty-stricken reality of Scotland in the seventeenth and much of the eighteenth century noting that there was a lack of a well-to-do population to buy goods produced: ‘An industry was thus dependent on export for any market beyond immediate domestic consumption’.[71] In addition to the impact of a limited domestic market and a failure to explore new markets there were several other factors involved in the decline of the craft in Dundee – both internal and external to guild operations. These included changing customer preferences and the bonnetmakers’ failure to adapt to market realities; the lack of formal guild rules for governing members and regulating apprentices; recurring problems in dealing with external competition; and new industry drawing bonnetmaker talent.

By the late eighteenth century headwear fashions were changing and Dundee’s bonnetmakers did not adapt to the new reality. Labouring men throughout Scotland had been wearing the flat blue bonnet for hundreds of years and it would have been reasonable for bonnetmakers to assume this would continue. Annette Smith opines that there is no indication they actively sought to address the declining popularity of their product:

They did not apparently try to alter their patterns or methods to accommodate new fashions. Nor do their own existing records give any inkling that they ever considered turning their skills to making other sorts of knitted garments.[72]

Gauldie writes that as the upper classes began wearing hats, the working classes began to emulate the new fashion, and that by the 1790s, parish ministers were reporting the wearing of cloth hats by men in the countryside as well.[73]

In The Industrious Revolution, Jan de Vries considers this emulation of style as a ‘social signal’. Referencing the American sociologist Thorstein Veblen, he writes that this form of consumption can be seen not so much as choosing the latest fashion based on personal need ‘…but for use as a social signal, or sign. …Indeed, economic growth only intensifies the demand for the positional goods that supply social comfort’.[74] Such choices were made possible by the growing prosperity brought about by Scotland’s Industrial Revolution. According to Stana Nenadic it was this new prosperity that accompanied the change in fashion, noting the documentation of this change in The Statistical Account of Scotland for the county of Aberdeen:

The dress of all the country people in the district was, some years ago, both for men and women, of cloth made of their own sheep wool, Kilmarnock or Dundee bonnets…Now every servant lad almost, must have his Sunday’s coat of English broad cloth, a vest and breeches of Manchester cotton, a high crowned hat, and a watch in his pocket.[75]

It is reasonable to believe that the bonnetmakers of Dundee did not foresee the impending changes in headwear fashion. Warden points to control of the craft by a small number of families, and it could be suggested by inference that this led to a narrow view of product and market possibilities.[76] They continued to rely on their shrinking single market, which was the working man who visited the Dundee burgh market and still favoured the blue bonnet.

The lack of formal guild rules for self-regulation can be seen as another factor contributing to the fate of the craft in Dundee: this is noted by Warden in his Burgh Laws of Dundee. In the contents of the trade’s new Lockit Book dating from 1660 he points to a weakness in respect of written rules:

The Bonnetmakers did not, either in any of their books or among their papers, possess any standard code of laws for the good government of the members in their dealings among themselves, or with those without the Craft. Neither did they have any formal rules and regulations for the guidance of their apprentices or journeymen.[77]

Minimal guidelines that did exist appear in their two Seals of Cause, which included a provision for electing a deacon from the membership, for electing members to act as senior masters and for these masters to put forth regulations in the form of ‘Acts, Statutes and Ordinances for the governing of the Craft and for the protection of its members’.[78] Gauldie notes an additional provision, which states:

…no man shall occupy the craft as a master until he be made a burgess and a freeman and examined and sworn by the deacon and masters of the craft that he be worth and that he have material and substance of his own to labour with.[79]

In their records there are no details describing the craft, no mention of product type and no instructions as to how bonnets are made – or how they should look. In apprentice agreements weights and sizes of bonnets are typically indicated, but do not appear elsewhere.[80] With so few regulations written into their founding documents, the trade would need to deal with problems – within and without the membership – as they arose. It is possible that written rules did in fact exist, but have not yet been discovered.

As noted above, in the Dundee burgh craft the deacon and elected senior masters would propose acts and statutes as needed, which would then be voted on for approval by the members. The insularity of this arrangement – control of the trade by a small number of families – likely meant that the focus in protecting the trade would also be narrow. In the next chapter, the system in Stewarton, Ayrshire will be examined: its deacon was the Baron of Corsehill, who was external to the craft, but knowledgeable of and influential in the larger social order. It could be argued that this arrangement would yield a more proactive and effective form of guild government.

From the late seventeenth century to well into the eighteenth the trade passed acts to deal with the most pressing problems arising within the membership. Examples included masters leaving the trade; issues with poorly dyed bonnets; and members purchasing bonnets externally to be sold as their own. In April of 1694 it was enacted that no one was to leave the trade unless they were unable to obtain work: any master doing so would bring the craft ‘…into disrepute [and]…shall for ever lose their liberty of the Craft’.[81] Later that year the deacon addressed the problem of poorly dyed bonnets with an act to deal with members circumventing proper dyeing to maximize profits.[82] In 1710 this problem was again addressed and another act passed.[83] When members of the craft purchased bonnets from Glasgow to sell as their own product in the burgh market – and to burgh merchants – the guild took this up as well. An act was passed in 1726 against Glasgow bonnets being sold in Dundee to control the supply of bonnets and protect the employment of Dundee bonnetmakers. Issues outwith the craft’s organisation were typically dealt with by negotiation and at times by the Burgh and Head Court, comprised of the deacons of the trades.[84] This included the persistent problem of external competition.

External competition plagued the Dundee bonnetmakers from the guild’s early years. Gauldie notes that most families of Hilltown’s ‘Bonnet Row’ produced bonnets and were outside the control of the craft in the Dundee burgh.[85] Bonnet knitting was not a particularly difficult craft to learn and the equipment required was inexpensive: ‘…a process so simple and easily carried on in the household, that many of them were surreptitiously made by unfreemen’.[86] This issue remained a problem for the guild throughout the sixteenth century until an alliance was formed with the local waulkers in 1589, who agreed to cease fulling the bonnets of the unfreemen of the Hill.[87] The cooperation of the waulkers led to a resolution of the problem when the bonnetmakers of the Hill paid entry money and joined the Dundee guild.[88] By the early eighteenth century, another problem with external competition arose, however – in this case with the tailor trade making cloth bonnets. In 1702 following a complaint by the bonnetmakers about unfair competition, the tailors agreed to cease production of the bonnets, noting – in what could be considered an unusual and generous gesture – that it was unfair to the bonnetmakers, as the cloth bonnets could be made faster than hand-knitted bonnets.[89] The issue arose again two decades later, in 1725 and the bonnetmakers lodged a complaint with the town council. Their demand that the tailors cease making cloth bonnets was denied.[90] In some form at least, then the issue with external competition had endured and the availability of cloth bonnets may well have been a contributory factor in the craft’s downturn.

The failure of the bonnemakers to avail themselves of additional markets contributed to the fate of the industry as well and can be traced back to the guild’s early years: this includes the lack of participation in an export market made possible by Dundee’s shipping activity. A.H. Millar, in The Compt Buik of David Wedderburne describes Dundee as a vibrant seaport between 1587 and 1630, and the prominent merchant as having a ‘…large business connection in Norway, the Low Countries, France, and Spain’.[91] Bennett notes that in examining these shipping records bonnets were never mentioned in lists of goods exported.[92]

Throughout this period there was no evident attempt by guild masters to seek markets farther afield – or to develop alternative products for the existing market.[93] An inability to secure the military market for headgear also contributed to the local industry’s demise. Although Dundee bonnetmakers supplied Highlanders with bonnets up to the time of the Battle of Culloden, Gauldie writes that soon afterward they lost this market: ‘When the regular Highland regiments were raised in the later eighteenth century Dundee lost to Kilmarnock and Stewarton the chance of equipping them’.[94]

An over-reliance on a single product and market would eventually lead to the end of the bonnetmaking industry in Dundee. The Dundee bonnetmakers would continue to supply their traditional market of working-class men who preferred the sturdy, weather-resistant bonnet – but the demand was not sufficient to yield a viable standard of living.[95] As demand for the traditional blue bonnet dwindled, affordable new headgear styles were made possible by the impressive ‘take-off’ in linen textile production: Miller notes that: ‘…in 1778 there were 4,000 linen looms in Glasgow and its environs…and 2,000 at Dundee [and]…50,000 operatives employed throughout Scotland in 1803, a figure which represents a six-fold increase on the number of weavers in 1792’.[96] As this industry gained a solid footing, Dundee’s remaining bonnetmakers were drawn to the burgeoning demand for weaving, where a more reliable source of income awaited: ‘…the volcanic growth of the flax and jute industries drew home workers into the factories and bonnet making was abandoned’.[97]

In 1793, the entry for Dundee in The Statistical Account of Scotland makes note that the burgh’s main item of manufacture was linen ‘…of various kinds – Osnaburghs, and other similar coarse fabrics for export’.[98] There is no mention – even historically – of bonnetmaking. According to de Vries, a vital part of this transition was the move away from the control of production and distribution by guilds to a more free market-based system that was an integral part of Scotland’s Industrial Revolution.[99] The apprentice arrangement that developed craft masters for trade guilds began to be replaced by opportunities for those outside the system to participate in more gainful employment.[100]

Several internal guild factors – as have been introduced above – can be seen as having stifled potential expansion of and contributed to the decline of bonnetmaking in Dundee. From the earliest days of the incorporation – and likely prior to it – a small number of families controlled the craft: as has been noted there were no evident rules for self-government in the founding documents or for dealing with inevitable external threats; and this insular group never wavered from its narrow view of product and market. Although establishment of the guild was essential in the development of bonnetmaking in Dundee, inherent weaknesses – both in the management of internal processes and product marketing – can be seen to having played a major role in the decline of the craft as more industrialised activity took prominence and provided alternative employment opportunities.

Chapter 2:

Stewarton Bonnetmaking and the Role of the Local Bonnet Court in the Trade’s Success through the Eighteenth Century

By the mid-eighteenth century bonnetmaking in Dundee was in serious decline while production was on the rise in Stewarton, where the guild was introducing a new style of headwear, knitting bonnets for the military market and would soon be exporting to Ulster and the northern colonies across the Atlantic.[101] The men of Stewarton had been producing bonnets since at least the end of the sixteenth century – if not earlier – and records of the guild there date from the seventeenth.[102] According to the Stewarton entry in The Statistical Account of Scotland from 1793, bonnetmaking had been the preeminent commercial activity in the town for a century or more:

…the chief trade in this place, and has been, it is said, for over 100 years, is bonnet making, which employs a great number of hands. They make also what are called French or Quebec caps. Besides supplying the country and the Highlands with these articles, large quantities are exported, which turn out to good account…[103]

As was seen in the last chapter, one of the possible factors contributing to the demise of bonnetmaking in Dundee was a weakness in providing for self-governance: there was a bare minimum of regulations in their charter, a guild dominated by a small number of families and a deacon selected from within the membership. Occasionally issues with an impact on the craft were dealt with externally, by the Burgh and Head Court. Stewarton’s guild membership, on the other hand was somewhat larger and more diverse and the Bonnet Court played a significant role in the management of the affairs of the local bonnetmakers. Its deacon was not a guild master, but the baronet of Corsehill, who was able to bring a broader perspective to the management of the trade.[104] Given his social standing the deacon would likely have had influence throughout the region, creating opportunities, which the bonnetmakers may not otherwise have had. Enid Gauldie opines about the Bonnet Court’s role in Stewarton’s success: ‘the bonnetmakers were helped…especially by the setting up of a very effective and well-regulated Bonnet Court’, and she continues that the ‘…Bonnet Court negotiated with the craft guilds of Glasgow to allow Stewarton bonnets to be sold in Glasgow markets without the usual restrictions’[105]. The Stewarton guild controlled production during times of low demand to stabilise prices, introduced new products and worked to create new markets. This chapter is concerned with the following question: How did the Baron Court of Corsehill factor in Stewarton’s bonnetmaking success through the eighteenth century?

The numbers of bonnetmakers in the small town of Stewarton increased through most of the eighteenth century: as Lamont reports, by 1729 the guild comprised 35 members[106], or slightly more according to Bennett, who notes that by the end of the 1720s there were 37 bonnetmakers present at a meeting that dealt with the low demand for bonnets at that time.[107] She adds that by the late 1720s there was a lack of work available to the Stewarton bonnetmakers and that they ‘were in difficulties’: this is confirmed by a poll taken at a 1730 meeting of the Court, finding that 15 members had work and 20 did not.[108] According to the minutes of the Bonnet Court in 1758, the membership totalled 29.[109] The number of masters in the larger Dundee burgh was somewhat lower: ‘Throughout the seventeenth century and until the middle of the eighteenth, the number of practising bonnetmakers fluctuated only slightly, from fourteen at lowest to 26 at the most’[110]. At any time in the history of the Dundee craft, there were three family surnames that represented half of the membership.[111] In Stewarton, on the other hand a total of 37 surnames were represented in the Bonnet Court minutes from 1673-1771, with the most frequently occurring surnames shown in the Table 2 below: from the data reviewed, six surnames represented 68 percent of the total mentioned.[112]

| Stewarton Bonnet Court Minutes 1673-1771 | ||

| Surname | Number of Mentions | Number of Years |

| Wylie | 168 | 98 |

| Picken | 157 | 68 |

| Caskie | 118 | 98 |

| Dunlop | 99 | 98 |

| Lachland | 76 | 98* |

| Currie | 69 | 98 |

| Early Years (1673-1704): | ||

| Pudzean | 33 | 31* |

| *In both instances it can be seen from wills and testaments available that these families were involved in bonnetmaking well before the period covered by the Court minutes.[113] | ||

Table 2: Stewarton bonnetmakers: frequently occurring surnames

It could be argued that in contrast to the narrow view of the Dundee trade’s possibilities – a product of a small number of families controlling the craft – the Stewarton experience benefitted from the viewpoints of a larger number of families populating the craft over an extended period of time – although the overall number of masters was never very great.

Stewarton bonnetmakers likely enjoyed a somewhat higher standard of living than the Dundee masters, as a look at their testaments demonstrates. Helen Bennett, in ‘Origins and Development of the Scottish Hand-knitting Industry’ notes that the first testament of a Stewarton bonnetmaker was that of Margaret Fultoun, relict of David Biggart, dated 15 February 1606:

…the couple are described as ‘tua puir cotteris’ [two poor cottars] and the largest part of their few goods was a quantity of lambswool and ‘certane raw unwalkit bonattis’ [unfulled bonnets], together worth 20 pounds.[114]

For the period 1600 to 1850 an additional seven testaments of Stewarton bonnetmakers appear on the National Records of Scotland database: as with the testaments of Dundee bonnetmakers the relative wealth of these individuals is seen at the time of their death. The 1612 testament of Archibald Pudzean(e) lists a moveable estate valued at £1,129 16s 8d – a sizable sum in respect of the two other Stewarton testaments from that century.[115] This value also far exceeds those of the Dundee masters mentioned in Chapter 1, dating from the same time period (all with values under £100)[116]. In his testament there is no specific mention of bonnetmaking-related items – only the debts owed by the deceased such as house and yard rent, oatmeal and servants’ fees.[117] A second testament, dated 1665 is that of John Lauchland, whose moveable estate was valued at £122 6s 8d: again, the debts owed by the deceased comprise rental on his bit of land and amounts to servants.[118] Another Pudzean testament – that of Andro Pudzean – is dated 1669 and shows a moveable estate valued at £153 10s including rents payable on lands owned by him.[119] The one available testament from the eighteenth century is that of Hugh Dunlop – another family name appearing prominently in the guild records: it is dated 1765 and shows a moveable estate value of £4 sterling, but provides no detail of interest other than the sum was actually in the hands of a Stewarton merchant.[120] The value of John Picken’s moveable estate in 1820 was £597 15s 10d, with principal amounts and interest due the deceased comprising most of the total.[121] Alexander Caskie (1819) left an estate valued at £420 18s 8d, which comprised farm-related crops such as corn, hay, potatoes and ryegrass, as well as bonnetmaking items including wool and finished bonnets.[122] In 1843, the testament of his relict, Jean Aitken did not list any bonnetmaking items but showed an estate valued at £541 15s 6d.[123] The moveable estates in these testaments generally demonstrate values greater than those of Dundee bonnetmakers of the same period. It should be noted, however that overall these were families, who earned a modest living.[124] Members of the Stewarton guild were also likely to be farmers, with bonnetmaking providing supplemental income.[125] Bennett writes about this:

An unusual feature revealed by the testaments of the Stewarton bonnetmakers is that bonnetmaking was only one of their activities: as might be expected in a rural area, all of them had livestock, and many had arable land as well, and it is evident that their income was derived from more than one source.[126]

The original records of the Bonnet Court that are available date from 1673 to 1772 and provide the basis for the analysis, which follows, of regulations enacted relative to the control of production and quality and the introduction of new products – as well as insight into the bonnetmakers’ relationship with the Glasgow guild. According to an entry in the Dictionaries of the Scots Language the Court actually dates from 1549.[127] Sir Andrew Cuninghame (1505-1544) was named the first laird of the house of Corsehill in 1532, and was followed by Sir Cuthbert Cuninghame (1532-1575) the second laird, who would have been the first deacon of the Bonnet Court according to this dating.[128] Four baronets of Corsehill presided over the Court as deacon during the 100 years covered by the Court records.[129] In the minutes of the 1674 meeting, Sir Alexander Cunningham, the first baronet of Corsehill was noted as the deacon – and he governed the proceedings of the Court until 1685.[130] He was followed by another Sir Alexander Cunningham, the second baronet, who was the longest-serving deacon, presiding over the Court for 45 years – from 1685 until 1730. The third deacon was Sir David Cunningham, chairing the meetings from 1730 to 1769; and the fourth, Sir Walter Montgomery-Cunningham, was deacon from 1769 to at least 1772 when the Court minutes come to an end. The length of term of most of these deacons would indicate a measure of consistency in overseeing matters of importance for significant periods of time.

The deacon was supported in his role by a baillie – his deputy – selected from the membership. During the first 64 years of the Court’s functioning (1673-1736) the role changed hands frequently, but the bonnetmakers acting in this capacity were from among the most prominent bonnetmaker surnames: Wylie, Pudzean, Picken and Caskie, among others. Andrew Picken acted as baillie for the subsequent 36 years – at least through to the end of the available minutes.[131]

The Court met annually and in many instances convened two or more times per year: a total of 146 meetings were held during the 100-year period.[132] In a meeting in 1687 the deacon – the second baronet of Corsehill – recognised the importance of regular gatherings of the membership in maintaining the discipline necessary to ensure the guild’s success: he determined that two meetings per year were to be held henceforth:

Two courts to be holden for the good of the s[ai]d trade to witt one yearly one the last Tuesday of June before the faire of Glasgow and another one the first Tuesday of Jan[ua]ry before the tuentie day of thin ane other faire in Glasgow.[133]

As can be seen from a meeting frequency analysis, this did not actually occur: the Court met twice annually for only 19 of his 45 years as deacon.[134] All matters relating to the regulation of production and marketing of bonnets were addressed at these meetings, usually with provisions made for the period until the next Court session would be held. In order to ensure that all members participated in meetings of the trade, the deacon found it necessary to stipulate that attendance at meetings be required.

The importance of the relationship between the Stewarton and Glasgow guilds is apparent when reading through the minutes: the participation of guild members in the twice-yearly Glasgow fair – typically in January and June or July – featured prominently.[135] Bennett writes about the arrangement made between Stewarton bonnetmakers and the Glasgow guild: ‘…the first indication that bonnetmaking there had been put on an organised basis is an agreement dated 24 April 1650, allowing Stewarton bonnets to be sold in Glasgow.’[136] The overarching reason behind this arrangement was inadequate local demand for Stewarton bonnets and an inadequate supply of bonnets in Glasgow. Bennett notes:

…it is apparent that by the middle of the seventeenth century their output went beyond the needs of the inhabitants of the immediate area…the Glasgow Incorporation virtually disappeared at the end of the seventeenth century…[137]

Regulations in respect of participation in the fair appear in most of the minutes throughout the period. Dates, locations and fees were set – as were penalties for non-compliance. The fee for entry was noted, for example in the 1670s: ‘Tradesmen to pay 40 shillings entry fee to Glasgow fair’.[138]The date and time of entry was typically specified as well as the fine for defying the regulation: ‘Non of the trad goe to Glasgow Fair until Monday next being the thred of july next after the sun rising under the pain of ten merkes Scots money’.[139] The specific location for selling their wares was often mentioned, such as an instance in which the bonnetmakers were told ‘…to goe alongst the bridge’.[140]

The control of production volume was an important issue dealt with during Court sessions. As Lamont writes, this was to prevent lower product prices due to oversupply: ‘…the Court would order all work to be stopped in the town, a practice known as an idlesett.’[141] The deacon’s method for doing this was to propose the pause, which was then enacted by membership approval and enforced by his baillie, who would issue fines and other penalties for non-compliance. Idlesetts were enacted at least 23 times between 1673 and 1771, with durations ranging from two to six weeks: penalties for making bonnets during an idlesett ranged from five to 15 shillings for each day’s offence.[142] One of the first entries in the Court’s minutes for 1673 indicates that there was to be an idlesett of two months: ‘No unauthorised bonnets to be made from Martinmas until 13 January under penalty of fine and confiscation of bonnets…’[143] Control of production was essential in preventing an oversupply of bonnets in the market – and thereby a drop in prices, resulting in a loss of bonnetmaker income. It was not until 1729 that a pause in bonnetmaking was enacted again. There were four meetings of the Bonnet Court that year, and during the January session a significant financial penalty was set for unlawful production – and provision was made for the poor as well:

The s[ai]d day it is enacted that ther be an idelsett of the whol trade beginning the 22 instant & to last till Candelsmess the poor of the trad being taken to consideration what they shuld be suplide with doring the s[ai]d time of idelsett…this to be observed under the penaltie of fifie pund Scots.[144]

When a poll of the membership was taken on 29 June 1730 it was learned that 20 of the 35 members present were without work – likely due to overproduction of bonnets by some of the members.[145] Two meetings were held that year, with the final session enacting an idlesett of one month, carrying the same hefty penalty as was set in the meetings of 1729 and declaring that the membership should ‘…maintain the poor of the trade out of there oun proper pockets…’[146]

The quality of headwear produced was an overarching concern and addressed regularly at Bonnet Court meetings – in respect of wool standard and dyeing and product weight. The quality of the wool used was an issue in the earlier years: from 1687 to 1706, on five occasions the membership approved regulations to counter the practice of degrading the quality of the wool by mixing in hair.[147] In 1688, for example, the act read in part: ‘No persone or persones in tyme comeing be found to mix hair with bonnet wooll…’[148] The penalty was a fine of ten pounds. It is probably safe to assume that this problem did not persist into the eighteenth century, as no further mention in the minutes is noted. Bennett notes that ‘…there are frequent injunctions about dyeing…’[149]Examples of actions in respect of dyeing restrictions can be found during the period 1690 until 1710, although after that date there are none further until the 1750s: specifically members were not permitted to purchase white wool and dye it black, nor to purchase any white or grey wool that had already been dyed black.[150]

A new product inaugurated by the bonnetmakers of Ayrshire in the 1720s injected new life into a trade that was dying out elsewhere in Scotland: Bennett writes –

While the craft elsewhere had declined to a small remnant, the knitters of Kilmarnock and Stewarton, in about 1720, had found a new product, the nightcap, which enabled them to survive the lean years. Roughly conical or bellshaped, plain or striped, the nightcap was the everyday dress of working men and sailors.[151]

The first mention of this new product in Stewarton appears in the minutes of a 1736 meeting, when two of the members were named the first inspectors of the caps.[152] The deacon found it necessary to appoint officers – inspectors in particular – to oversee the conduct of members in production and trade. Lamont writes about this:

The weight and quality of the Stewarton bonnets was important and to ensure that they were up to the high standards demanded in Glasgow, the Bonnet Court of Corsehill appointed inspectors, known as sichers. Their job was to inspect and approve the caps…When some traders complained of having received ‘wet caps’ (bonnets soaked in water to make them heavier) the makers were duly fined.[153]

Two years later, in 1738 the Court described how the caps should be made and specified what they should weigh: a penalty of £6 Scots per dozen was established for failing to meet these standards and the faulty caps were to be seized.[154] Four inspectors of the caps were named for the ensuing year, and that number varied between four and six each year until 1772, with the exception of 1743 when 10 inspectors were named.[155] The inspectors were responsible for confirming that products were identified with the maker’s mark and to seal the lot before they were sent to the mill to be fulled.

The cap became increasingly popular: in 1744 the membership unanimously agreed to make caps in place of bonnets: ‘…whoever shall make any bonetts during the s[ai]d six weeks shall forfeitt half a Merk Scots for each bonett so made.’[156] The apparent consumer preference for caps is seen through the remainder of this period, with bonnets still produced but subject to continued idlesetts: ten more instances are documented between 1752 and 1769, when making bonnets was subject to penalties.[157] An example is taken from one of the Court’s meetings in 1755:

…its hereby declared that whoever inclines to make Caps the may work att ther leisure and itt is furder Declared that in Caise any person making bonnatts during the four weeks above mentioned shall be liaable in the soume of three pounds Scots for each Dozen so made…[158]

Other examples can be found of fines for making bonnets during these pauses – such as in 1760, 1761 and 1768 when the fine was five shillings sterling for each day’s offence.[159]

The issue of underweight headwear was also addressed by the Court. Bennett writes of the trade dealing with the problem at a meeting of the Court in 1738: it was enacted that ‘The bonnets themselves had to be of a certain weight and standard of finish, and substantial fines were imposed for under-weight products…’[160] This issue would arise nine more times at Court sessions between 1739 and 1769, all in respect of caps, rather than bonnets. In 1739, for example a member was found to have produced two and half dozen caps of insufficient weight: the caps were seized and the bonnetmaker was fined £10 Scots per dozen.[161] The deacon ruled that if he or anyone else did not pay the fine levied they were to ‘…goe to prison till paytt’.[162] In an unusual action, the members agreed in 1769 that caps of insufficient weight that were confiscated would be sold on to merchants at a reduced rate and the merchant would be allowed to sell them at a suitably discounted price.[163] This remedy had not appeared in the minutes previously.

Product pricing standards were addressed in the 1750s, and in the four instances when regulations were enacted the selling price for caps was set.[164] Historically, pauses in production had been enacted to maintain stable product prices; however in 1752 the price was set at 5s 8d per dozen when sold to a merchant or reseller, and in no case under 6s per dozen at market: the penalty for contravening this regulation was 5s sterling per dozen.[165] In 1768 the price was set no lower than 6s 6d, with a penalty of 8s sterling per dozen; 6s 8d in 1769 and 7s 6d in 1771, with the penalty reduced to 1s per dozen.[166] There were no instances documented of bonnet prices being regulated.

The final quality issue to be dealt with by acts of the Court related to the dyeing of caps. During a meeting in 1750, it was enacted that for ‘scarlet, orange and other tints’ the only dye to be used was cochineal, at the risk of a fine of six shillings per dozen.[167] In 1756, members voted to prohibit the dyeing of caps blue with any substance other than indigo, with a fine of 20 shillings per item levied: the reason given was that the colour would fade in rainy weather.[168]

It was noted in Chapter 1 that external competition was problematic for the bonnetmakers of Dundee from the incorporation’s early years. This was also an issue that Stewarton’s Bonnet Court would need to address, although it was not as troublesome as in Dundee. In 1706 the Bonnet Court enacted a prohibition against bonnets being made for sale by people who were not members of the trade, or could not show that their fathers were members.[169] Buying bonnets outside the guild for resale – actually another form of external competition – was also addressed. A severe penalty was enacted for this practice: ‘…a fine of £50 Scots and permanent expulsion from the Incorporation – was reserved for those who bought bonnets in Kilmarnock and sold them in Glasgow as Stewarton products’.[170]

The minutes available from the Bonnet Court cease in 1772, but Bennett writes that the Court likely continued to function until 1785, when ‘…the Stewarton bonnetmakers, who had formerly been governed by the Corshill Bonnet Court, formed themselves into the Bonnetmakers’ Society of Stewarton’.[171] The Bonnet Court had been central to the prospering of bonnetmaking in Stewarton – from establishing a productive relationship with the Glasgow guild to ensuring the quality of Stewarton’s products – and was likely responsible for providing the foundation for continued success well into the nineteenth century.

Chapter 3

Product and Market Diversification and the Endurance of Stewarton’s Bonnetmaking into Scotland’s Industrial Age

As was noted in the previous chapter, by the 1720s the Stewarton bonnetmakers were experiencing a decline in demand for their bonnets: this was addressed by the Bonnet Court with pauses in production, which reduced the number of bonnets available for sale and helped stabilise the product price. It was necessity – and entrepreneurship – that led to the development of a new product to address a change in headwear style preference and reinvigorate their business. The customer was still the Scottish working man, who wanted to emulate styles worn by the more well-to-do, and the Ayrshire bonnetmakers created what was called a nightcap – a bit of a misnomer as it became part of everyday dress.[172] The cap is described by Bennett as ‘conical or bellshaped, plain or striped’, adding that the ‘…new product… enabled them to survive the lean years’.[173] A cap of this style is worn by the central figure in the illustration below.

Figure 3: David Allan’s Illustration to Allan Ramsay’s ‘The Gentle Shepherd’: Bauldy Describes His Fright. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Through the latter part of the eighteenth century there was still a limited domestic market for the traditional blue bonnet, however: for ‘…such important occasions as attending church or a funeral, or going to market…a broad blue bonnet …was worn instead.[174] This new ‘cap’ style in hand-knitted headwear was introduced as bonnetmaking was on the wane in Dundee and other parts of Scotland.

It can be argued that the longevity of bonnetmaking in Stewarton was the result of three factors: the introduction of a new product to meet new demands from the traditional market; the move into a new market with a range of military bonnets; and the exploration of possibilities in international trade. In the current chapter the question addressed is this: In what ways was the Stewarton bonnetmakers’ diversification of products and markets responsible for its survival into the Industrial Age?

A new product – the nightcap – is first mentioned in the minutes of Stewarton’s Corsehill Bonnet Court in 1737, when the first two visitors (inspectors) of the caps were appointed by the deacon.[175] In the following year, the minutes show that a weight for the caps was set and a penalty for caps that were lighter than this was enacted: ‘…in Caise they shall be lighter they are not to be sealed as after to forfeitt On shill sterling for each Dozen…’[176] By 1738, the method for knitting a cap was stipulated in the Court minutes as well:

‘…each Cap shall have threescore of loups upon each needle and three score of bouts [rounds of knitting] and nine bouts afterwards and the rest to make the Cape shapely to the Crown and furder twenty eight bouts to the upfall [back of neck]…’[177]

Cap production had become so successful that at a guild meeting in 1744 ten visitors of the caps were appointed.[178] By the 1793 entry in The Statistical Account of Scotland it was noted that bonnetmaking had been the main commercial activity in Stewarton for a century and in addition to the domestic market, the bonnetmakers were supplying international markets with large quantities of ‘French or Quebec caps’.[179]

Due to decreasing demand for the traditional product pauses in bonnet production were required throughout the mid-eighteenth century. At a Court session in 1744 it was unanimously agreed that caps – rather than bonnets – would be made for a period of six weeks: The minutes read:

The s[ai]d day the whole Corporatione with Consent of the Deacon having Maturely Considered that the making of Caps will be a great advantage to the trade They therfore with on voice unanimously agreed that they shall make sufficent Caps fir six weeks after the third day of December first to Come and whoever shall make any bonetts during the s[ai]d six weeks shall forfeitt half a Merk Scots for each bonett so made…[180]

Bonnet Court records show that between 1743 and 1772 there were 23 instances of the making of bonnets being prohibited during certain periods, and only the production of caps being allowed: more than half of the idlesetts occurred between 1767 and 1772.[181]

New markets for Stewarton headwear were also essential to ensure the guild’s success – and were secured through the efforts of the Bonnet Court – including the important access to Glasgow fairs and markets. Earlier, in the seventeenth century – ‘The Glasgow Guild gave trading rights to the Bonnetmakers of Stewarton, marked each year by the Glasgow Deacon’s involvement with the Stewarton Bonnet Fair.’[182] They were granted limited annual licences to trade within the boundaries of the Burgh of Glasgow on market days for a payment known as the ‘broadpenny’, and to carry on unrestricted trade at burgh fairs.[183] Until the latter part of the eighteenth century the Stewarton guild depended on the domestic market for its headwear and in order to ensure continued success of their enterprise an export market was needed. Isabel Grant in ‘An Old Scottish Handicraft Industry’ opines on the importance of international trade: ‘An industry was thus dependent on export for any market beyond immediate domestic consumption [and]…easy access to a port was a necessity in order to carry on such a trade.’[184] According to Philipp Rӧssner growth in export trade from the west of Scotland was sustained from the 1730s and interrupted only in the short term by the American Revolution.[185] By mid-century shipping trade from Glasgow was heavily focussed on the Atlantic colonial markets rather than the Baltic.[186] By the 1790s Stewarton’s access to overseas markets by way of Glasgow’s burgeoning shipping trade was at least partly the result of the guild’s relationship with William Wilson and Son, an important tartan manufacturer in Bannockburn.[187]

In conjunction with developing new products and new markets, ensuring the quality of Stewarton’s headwear was essential – and was regularly addressed by the guild. This was not always the case with other Scottish woollen goods produced during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries however, which were reportedly of low quality. The export of cheap – and lower quality – woollen goods was important to the Scottish economy, from the Baltic and continental European markets prior to the Union of Parliaments in 1707 to the new markets on the other side of the Atlantic in the latter part of the eighteenth century.[188] T.C. Smout, in ‘Making and Trading Dress and Décor in Seventeenth-century Scotland’ bemoans the quality of Scottish textiles produced during that time: ‘Woollens and linens, yarn, cloth, bonnets and stockings, with clear regional specialisations, were manufactured, but they were all of low cost and quality’.[189] By the middle years of the eighteenth century standards were not much improved even with the efforts of the Board of Trustees for Manufactures established following the Union of Parliaments.[190] As M.L. Robertson notes, this problem continued into the latter years of the eighteenth century, when Glasgow manufacturers and merchants joined hands to ‘…protect and encourage Scottish trade and manufactures…’[191] It is reasonable to believe, however that bonnets and caps produced by the Stewarton guild were of a higher quality given the strict monitoring of standards by inspectors appointed by the deacon of the Bonnet Court. Bennett notes: ‘…the army also required a high degree of uniformity in colour and pattern. That the bonnetmakers were able to meet this requirement speaks for the flexibility and organisation of the trade…’[192] High quality standards would have been essential for Stewarton to be successful with its military headgear.

This new market – and modified product – began to occupy the efforts of the Stewarton bonnetmakers as the guild became the main supplier of military headwear.[193] Early on Dundee bonnetmakers supplied Highland soldiers with headwear, but by the mid-eighteenth century it was the bonnetmakers of Stewarton who had taken over production: these were the famous ‘Blue bonnets over the Border’, which were mostly made in Stewarton, although known as ‘Glasgow Bonnets’[194] This was yet another sign that bonnetmaking in Dundee was nearing its end and an indication that the Stewarton guild was becoming the leader in Scotland’s production of military bonnets. The military-style bonnet is first mentioned in the Stewarton Bonnet Court minutes in 1750, and it is in respect of the quality of wool to be used: ‘S[ai]d Day the Company of Bonent makers has ag[reed] that no cocked bonetts be made under the penalty of three pound Scots fine for each Dozen cut of [good?] wool except the necks.’[195] Although not specifically mentioned as a military bonnet, it can reasonably be assumed to be, given the definition of a ‘cockit or cocked bonnet’ in the Dictionaries of the Scots Language.[196] Access to the military market can also be traced to the guild’s relationship with William Wilson and Son.[197]

Individual orders for military bonnets could be large: ‘…a letter from John Wylie in Stewarton dated 10 October 1798, for instance, records the dispatch of 988 bonnets for privates, and a further 71 for sergeants…’[198] The military segment of Stewarton’s trade was significant enough that by 1820 it reportedly employed 275 men as well as large numbers of women. [199] No mention is made in The Statistical Account of military bonnets, however until the entry in 1845, when it is stated that ‘Almost the whole regimental and naval bonnets and caps are made here…’[200] Bennett writes that the trade in military headgear was flourishing, noting that military bonnets comprised the bulk of the trade, compensating for reduction in demand for the traditional bonnet.[201] Innes Duffus concurs: ‘…the men of Stewarton were marketing their wares successfully to the army, which of course was the biggest market available’.[202]

An early example of a military bonnet can be seen in Figure 4, below – worn by the soldier on the left. The soldier on the right is wearing a more traditional bonnet.

Figure 4: Soldiers from a Highland regiment c. 1744: artist unknown, public domain.

The Stewarton guild became known for styles such as the Glengarry and the Balmoral, amongst others and were all knit to government specifications. Over time, the bonnets became more elaborate – following fashion – with enhancements such as dicing on the headband and plumes and rosettes attached; the bonnet was stiffened and the shape enhanced by the new headband style.[203]

…a bewildering array of types and patterns: bonnets were often made in three qualities – for officers, sergeants and privates; the basic colour was generally dark blue but sometimes altered to yellow, white or scarlet.[204]

Some of these enhancements can be seen in the photograph below (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Glengarry, Regimental Museum of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, Stirling Castle: Acc. No.0007a Date c.1854

In addition to the successful introduction their new products, by the late eighteenth century the bonnetmakers of Stewarton were engaged in overseas trade, represented by the firm of William Wilson and Son of Bannockburn for example, who opened new domestic and international markets for their headgear:

The firm of Wilson, tweed and tartan makers, sent agents into the Highlands and Islands to sell cloth and blue bonnets to the clansmen, and when the new Highland regiments were to be kitted out it was the Stewarton trade which supplied them with bonnets and later glengarries.[205]

By the 1790s the firm was reported to have developed a considerable trade in supplying military wear to Highland regiments and in exports to North America – and purchased all of its bonnets and caps for resale from the bonnetmakers of Ayrshire.[206] Stewarton bonnets ‘…start to show up in fair numbers in the Canadian (and later the western) fur trade’.[207] Gauldie notes that a product known as the ‘Quebec cap’ was part of the headwear exported.[208] Exports from Scotland were finding new inroads to North America ‘through Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Canada’.[209]

Robert Cooper in his study of the Hummel bonnet writes that although there are few bonnets, which have survived from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists of that era have captured the popularity of the bonnets in North America as well:

…and reveal the popularity of a knitted bonnet not only with the Europeans, but also with native tribes. The bonnets were imported into North America by the Hudson Bay Company as articles of trade and have been identified as being used in diverse areas of North America.[210]

See Figure 6 for sketches of Scots bonnets worn by Native men.