This is the third in a series of three posts. The focus this time is the textile heritage of Northeastern Thailand (Isan). Unless otherwise indicated, all photos are ©Michael Harrigan.

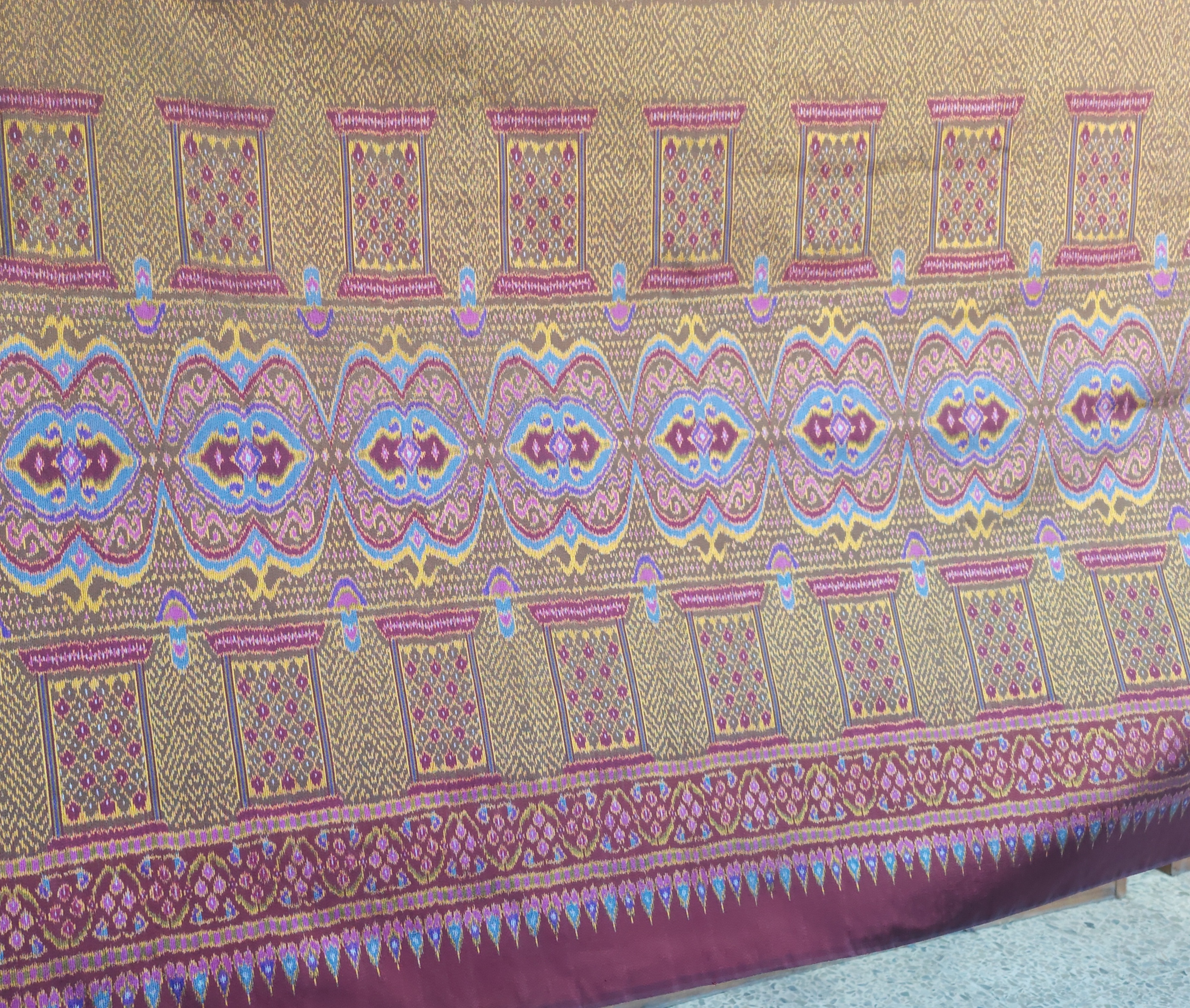

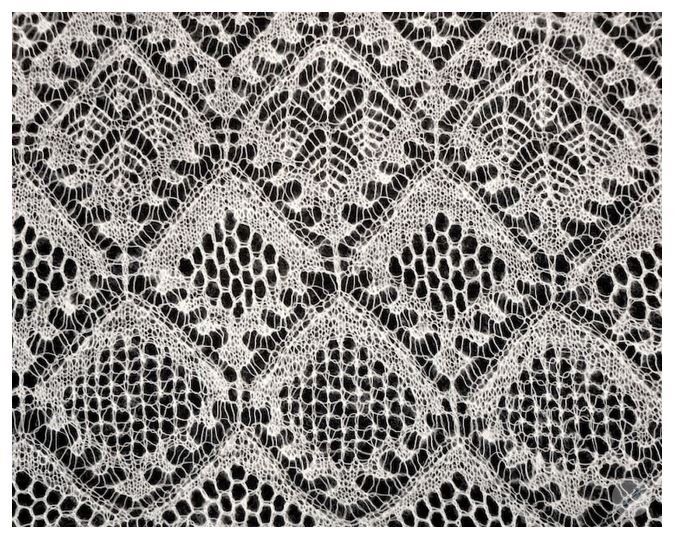

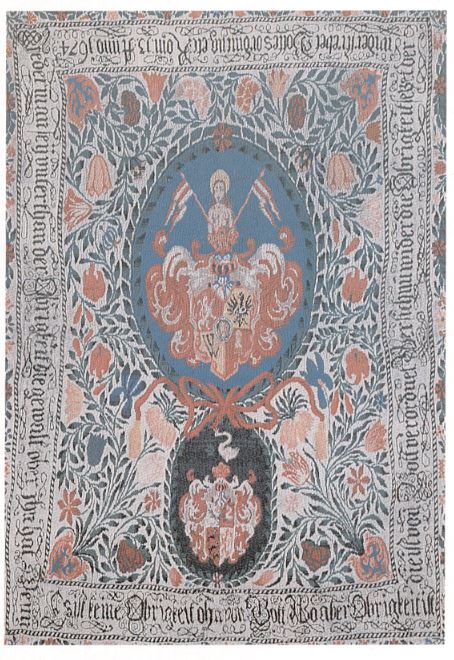

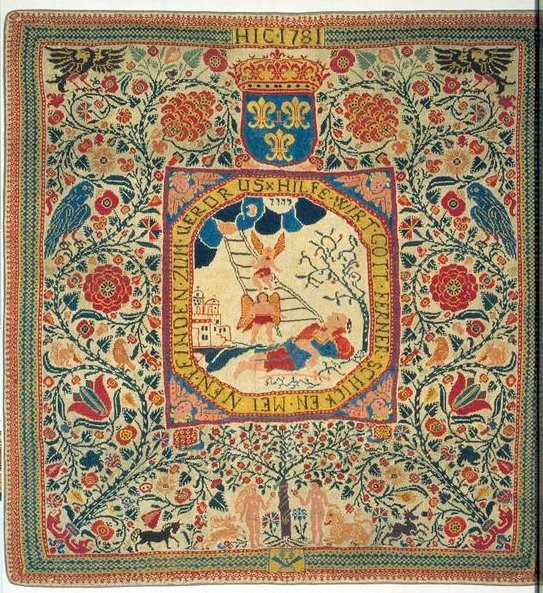

Weaving has been a way of life for many generations in Isan villages. The number of ethnic groups in the region has led to a multiplicity of weaving styles, often with each village having its own distinctive style. The Northeast is well-known for mat mi (mud mee) textiles: a Thai ikat or tie-dyed technique.

As noted in an earlier post, to create mud mee designs the weft yarns are tied with strings at strategically-placed points before dyeing. The mud mee textile is considered the world’s oldest patterning technique for woven cotton and silk, dating back 3,000 years (coinciding with the first production of silk).

Mud mee silk is a staple of the Isan weaving industry: the technique known as phrae wa employs additional wefts of silk threads to create patterns in high contrast to a red background fabric. The Phu Thai ethnic people of Ban Poen village in Kalasin province are considered the masters of this technique. The textile is known as the ‘Queen of Thai Silk’ – and Isan silk has become known worldwide as Thai silk.

Ban Khwao in Chaiyaphum and Chonabot village in Khon Kaen province are known for producing the finest mud mee silks in the country. On a recent road trip to Isan we visited an exhibition of Khon Kaen weavers from the Chonabot district.

The Ban Chiang community in Udon Thani province produces indigo-dyed woven fabric. It is generally assumed that 5,000 years ago the inhabitants of the community knew how to spin fiber and dye and weave as well. The Ban Nong Kok community in Udon Thani produces cloth dyed with lotus petals.

We recently visited a silk weaving village in Surin province. Ban Sawai village is home to a SACIT-accredited craft center (Sustainable Arts and Crafts Institute of Thailand).

On the same trip we stopped at a fascinating SACIT-accredited center – Ban Tha Sawang – in nearby Khon Kaen province, where we were able to observe a master weaver with helpers creating fabric for which the village is so well known. This technique involves an additional weft of golden silk brocade, requiring more than 1,000 heddles and four to five weavers. We were told that only four to five centimeters of fabric could be produced each day. All work is by special order, and as you might imagine, is very pricey: these are considered some of the finest handwoven silks in the world.

In Ban Hua Fai – our third and final stop of that day – we were able to observe the village’s specialty, which is a technique called painted silk ikat. Rather than tying the weft threads before dyeing, designs are painted (with dyes) directly on the weft threads that have been wrapped on a frame.

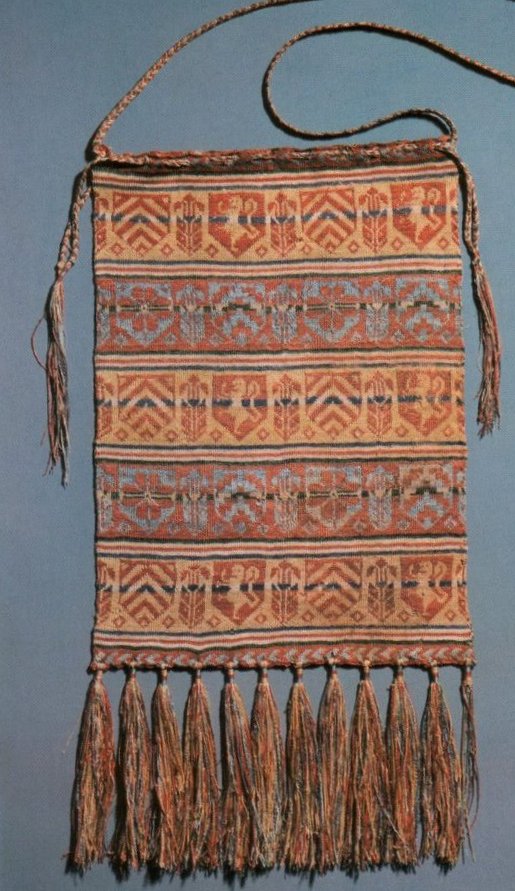

Silk textiles are undoubtedly the celebrated treasure of Isan, but handwoven cottons are also well represented. In addition to the ubiquitous indigo-dyed mud mee fabrics, an ancient technique known as khit is employed by cotton weavers in Nong Bua Lampu province. In fact, much more cotton is woven in the region than silk.

Another type of woven cotton is produced by the Prae Pan women’s group in Khon Kaen province. The women weave highly-textured, reversible cotton textiles using natural dyes. The Phu Thai ethnic minority in Nakhon Phanom province is also known for handwoven cottons.

Although this is the end of this series on traditional Thai textiles, we will undoubtedly be visiting more handweavers throughout Thailand – and when we come across something unique, we’ll share some photos and commentary.

Sources

Loha-unchit, Kasma, “A Treasure of Northeastern Thailand: Weaving Villages”, 30 May 2009, https://www.thaifoodandtravel.com/blog/posts/ne-thailand-weaving-villages.html

Thailand Foundation, “Mat Mii’, (created with special help from the Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles), https://www.thailandfoundation.or.th/culture_heritage/mat-mii/

The Nation, “A Trip to Thailand’s Silk Route”, 29 Dec 2019, https://www.nationthailand.com/thai-destination/30379968

The Support Arts and Crafts International Centre of Thailand, “Types of Thai Handicrafts: Painted Silk Ikat (Pha Mai Taem Mii)”, https://cms.sacit.or.th/cms/uploads/categories/5b3b3e573becfa5d7fac4916f8bc0fed/_86e53d5629200f55a3332ca9a8a18a48.pdf

Tourism Product Department, Tourism Authority of Thailand, “Pass on the Story: Textile Treasures of Northern Thailand”, https://www.tourismthailand.org/tourismproduct